Significance of Red Cell Count for the Detection of Thalassemia Minor

Department of Microbiology, Jinnah University for Women, Karachi 74600, Pakistan.

*Corresponding author:

Naheed Afshan;Email:

naheedafshan7@hotmail.comReceived: 03.Dec.2015; Accepted: 14.Mar.2016

Views 3767

Abstract

Thalassemia minor is known to be a hereditary disease involving affected globin chains. In Thalassemia minor, the fetus inherits haemoglobin genes during fertilization, each from the mother and the father, respectively. Individuals with a defect in one gene are known as carriers of Thalassemia minor. There are different procedures available for the detection of Thalassemia minor but most of them are expensive, so a study was designed at Microbiology department of Jinnah University for Women to check the total RBC count of known Thalassemia minor patients. In this study, one hundred (100) blood samples of known Thalassemia minor individuals were collected. The results showed increased levels of red cell count in Thalassemia minor patients as compared to the controls (normal persons) which were correlated with naked-eye single tube Red cell osmotic fragility test (NESTROFT). The results were further confirmed by the evaluation of red cell indices by complete blood count test. Thalassemia minor patients have hypochromic microcytic red blood cells with increased red blood cell number and they may have mild anemia but are usually asymptomatic. The main purpose of this study is to give awareness to our community about Thalassemia minor and its cheap diagnosis which can differentiate it from other types of anemia.

Keywords

Thalassemia, heterozygous, microcytosis, anemia.

Citation

Hamid, M., Nawaz, B., Afshan, N., 2016. Significance of Red Cell Count for the Detection of Thalassemia Minor. PSM Biol. Res., 01(1): 22-25.

Introduction

Thalassemia minor is said to be a monogenetic blood condition. Thalassemia minor patients are usually asymptomatic and lead a good life (Rachmilewitz and Giardina, 2011). A child develops Thalassemia minor when he/she inherits the defected gene from one of the parents, or a more severe form of Thalassemia (Thalassemia major) if the gene from both the parents has been inherited. The term “Thalassemia” actually covers a large group of inherited blood diseases which can be found commonly among people of Mediterranean and Asian origin. Individuals carrying Thalassemia have defects in the genes interfering with the haemoglobin production and ultimately that individual developsanemia. The most common among the subgroups of Thalassemia minor is Beta-Thalassemia minor. Beta-Thalassemia minor patients have only one copy of the defective gene. Some people with beta-Thalassemia minor experience mild anemia (Galanello and Origa, 2010) and may need to maintain their diets, but in normal case, most of the individuals lead a perfectly healthy life and there is no need for special treatment. In fact, many patients do not know that they are carrying the defective genes, unless they have been tested for it. There is mild anemia in the patients. Even with this mild anemia, patients often complain for weakness and fatigue of varying degrees (Clarke and Higgins, 2000).

Thalassemia minor is caused by defects in the genes that make haemoglobin. The type of defective gene is responsible for the nature of Thalassemia minor inherited by an individual. Beta-Thalassemia minor is caused by the reduction or the absence of beta globin synthesis (Thomas, 2001). Thalassemia patients usually lead a healthy life. Some cases of Thalassemia minor have occasionally been reported with splenomegaly, mild bone changes, leg ulcers, or cholelithiasis. Sometimes in pregnant women, significant anemia may develop which requires 1-5 mg/day of folic acid and supportive transfusion therapy (Rachmilewitz and Giardina, 2011). Some patients have complaints for fatigue. Diagnosis of Thalassemia minor can be done by many means such as by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) that is at molecular level, by performing osmotic fragility test (used in this study) and haematological based diagnosis. Treatment for Beta Thalassemia minor includes the periodic blood transfusions throughout the life of patients, combined with iron chelation. Blood transfusions should be given only when required (Nikam et al., 2012). Muhammad et al. (2013) found co-infection of diabetes mellitus with HCV and HBV. The risk factors linked with hepatocellular carcinoma include age, sex, diet, alcohol, and infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and/or hepatitis C virus (HCV) (Ali et al., 2015) that may result in thalassemia patients due to repeated blood transfusions.

Haemoglobin is a protein which has a molecular weight of about 68,000 Da (Determann, 1968) and pI at 6.8-7.0 (Gubbuk et al., 2012). It contains four approximately equal polypeptide chains (Gubbuk et al., 2012) which are identical in pairs. Several types of haemoglobin are produced in normal human developmental stages. These are haemoglobin A (Adult haemoglobin) and a subfraction A1, haemoglobin A2, fetal haemoglobin and embryonic haemoglobin (Muirhead and Perutz, 1963). The amount of HbA2 in a normal individual increases 2.5-3.5% of the total haemoglobin during the first and a half year of a child’s life (Mosca et al., 2009). HbA2 is used as a basis for the diagnosis of Thalassemia minor soon after it was discovered in 1950s (Kunkel et al., 1957).

Complete blood count (CBC) test results of Thalassemia minor individuals show low Mean corpuscular volume (MCV), Mean corpuscular heamoglobin (MCH) (Rathod et al., 2007) , the Red cell count is elevated, that is >5.0×106 μl and Red cell distribution width (RDW) is less 17% (Burdick et al., 2009) with the exception that Mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration (MCHC) is normal (Hussain et al., 2005). Blood smear shows basophilic stippling of erythrocytes (Peter and Rowley, 1976), microcytosis with or without mild anemia (O’Donnell and Ahuja, 2005). Usually the parasite of malaria (Falciparum malaria) grows inside the RBCs of a normal human and causes Malaria. But in Thalassemia minor, the patients have a protection against Malaria because the RBCs in the Thalassemia minor patients are fragile. The cells break down when malarial parasite gets inside and the parasite stops growing (Jacoby and Youngson, 2005). It has been estimated that the global prevalence of Thalassemia minor is at around 1.5% and the countries in which Thalassemia minor is most common, which fall in the “Thalassemia red belt”, include North and South Africa, Southern Europe, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and the Far East (Khosa et al., 2015). It has been estimated that the incident rate of Beta Thalassemia minor in the Pakistani population has met up to approximately 6% (Usman et al., 2011).

Materials and Methods

Sample collection

One hundred blood samples of known Thalassemia minor individuals were collected for the study. Blood samples were collected by the injection of a new syringe each time for each patient.

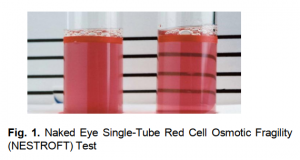

Naked-Eye Single TubeRed Cell Osmotic Fragility Test (NESTROFT)

Naked-eye single tube red cell osmotic fragility test (NESTROFT) was performed for screening of Beta Thalassemia minor which was also chosen by Sunil and his colleagues (Gomber and Madan, 1997). 100 sterile test tubes were taken containing 4ml 0.36% saline. 50μl blood was added in the tubes respectively. The tubes were left undisturbed at room temperature for 30mins. The turbidity in the tubes was observed in the presence of a tube light behind them. Turbidity shows whether the individual is Thalassemia minor or Iron deficient. For confirmation, CBC was done.

Complete Blood Count (CBC) Test

As per the recommendations given by International Committee for Standardization in Hematology expert panel, complete blood count (CBC) is an initial test for Beta Thalassemia minor diagnosis (Clarke and Higgins, 2000). Blood sample was collected in a test tube containing an anticoagulant (EDTA, sometimes citrate) to prevent it from clotting. The blood was shaken vigorously and placed on a rack in the analyzer (Sysmex KX-21). The blood components were analyzed and the results came out in a printed form. Blood counting machines aspirate a very little amount of the sample through small tubing. Sensors compute the number of cells passing through the tubing, and can determine the type of cell.

Results

The black line behind the test tubes containing blood was not clearly visible which indicates positive test (Figure 1) (Thalassemia trait/Thalassemia minor) due to the turbidity of the solution.

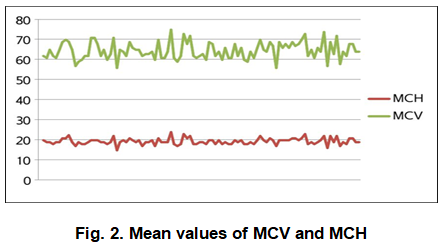

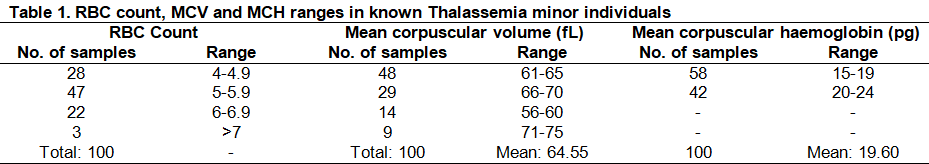

Significantly low Mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and Mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) (Figure 2) was found among all individuals with a mean of 64.55fl and 19.60pg respectively ( Table 1). MCV value <80fl and MCH value <27pg are the significant diagnostic parameters of Thalassemia minor.

The results showed normal RBC count [4.7-6.1 (M), 4.2-5.4 (F)] in 73.5% individuals and elevated RBC count in 24.5% individuals. Normal and elevated Red cell count with significantly low MCV and MCH indicates that the individuals are Thalassemia minor.

Discussion

It has been surveyed that Beta Thalassemia minor is very common in Pakistan (Khosa et al., 2015). There are a number of different procedures available for the detection and confirmation of Thalassemia individuals (Nikam et al., 2012) but most of them are much expensive and are not available in every diagnostic laboratory. Keeping these problems in mind, we evaluated the accuracy of inexpensive methods by known patients. In this study for the detection of Thalassemia minor carriers, Osmotic fragility test was carried out firstly.

Turbidity appeared in all tubes which means all the individuals were Thalassemia minor. It was confirmed by the CBC test that the RCC range in these patients was normal (73.5% of the total samples) and elevated (24.5%). By these results, we can differentiate Thalassemia minor from other types of anemia. In a previous study in Egypt, El-Beshlawy et al. (2007) found sensitivity and specificity of one tube fragility test as 87% and 34.1% respectively. The MCV and MCH ranges were significantly lower in cases of Thalassemia minor. All patients in this study had MCV values between 56-75fl with a mean of 64.55fl and MCH values between 15-24pg with a mean of 19.60pg. The normal values for MCV and MCH are 80-99 fl and 27 to 31 pg/cell respectively. Hence elevated RCC, MCV < 80fl and MCH <27pg are outstanding diagnostic criterion along with positive NESTROFT test in detecting Thalassemia carriers. Yamsri et al. (2011) showed MCV less than 80 fl and MCH less than 27 pg in Thalassemia carriers. Hb electrophoresis facility is lacking at many places in Pakistan. Red cell indices obtained from electronic counters can be reliably used in diagnosing Thalassemia. CBC provided by a routine automated blood counter is a major contributor for large-scale screening and convenient detection of carriers. They are cheap and easily reachable by individuals who are not competent in hematology.

Conclusion

Poverty in Pakistan has limited the population to get treatments for many diseases whose tests and medications are much expensive and unaffordable. As the tests for detecting Thalassemia minor at molecular level are costly for a lower-class individual, cheap tests such as NESTROFT and CBC are recommended which give an idea whether the patient has Thalassemia minor or not. The main purpose of this study is to give awareness to our community about Thalassemia minor and its cheap diagnosis which can differentiate it from other types of anemia. Various awareness camps and seminars should be arranged.

Acknowledgement

The authors are highly thankful to Jinnah University for women, Karachi, for supporting in the accomplishment of this study without any inconvenience. The authors are also thankful to Asfa Ashraf, Lahore College for Women University, Lahore for her kind contribution to improve this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

References

Ali, H.M., Bhatti, S., Iqbal, M.N., Ali, S., Ahmad, A., Irfan, M., Muhammad, A., 2015. Mutational analysis of MDM2 gene in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Lett., 3(1):33-36.

Clarke, G.M., Higgins, T.N., 2000. “Laboratory investigation of hemoglobinopathies and thalassemias: review and update.” Clin. Chem., 46(8): 1284-1290.

Burdick, C.O., Ntaios, G., Rathod.D., 2009. Separating thalassemia trait and iron deficiency by simple inspection. Am. J. Clin. Pathol., 131(3): 444-445.

El-Beshlwy, A., Kaddah, N., Moustafa, A., Moukhtar, G., Youssry, I., 2007. Screening for β-thalasaemia carriers in Egypt: significance of the osmotic fragility test. East Mediterr. Health J., 13(4): 780-786.

Determann, H., 1968. Gel Chromatography: Gel Filtration, Gel Permeation, Molecular Sieves A Laboratory Handbook, Springer. pp.195.

Galanello, R., Origa, R., 2010. Review: Beta-thalassemia. Orphanet. J. Rare. Dis., 5(11): 1-15. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-5-11

Gomber, S., Madan, N., 1997. Validity of nestroft in screening and diagnosis of β-thalassemia trait. J. Trop. Pediatr., 43(6): 363-366.

Gubbuk, I.H., Ozmen, M., Maltas, E., 2012. Immobilization and Characterization of Hemoglobin on Modified Sporopollenin Surfaces” Int. J. Biol. Mac., 50 (5): 1346-1352.

Hussain, Z., Malik, N., Chughtai, A.S., 2005. Diagnostic significance of red cell indices in Beta-thalassemia trait. Biomedica, 2: 129-131.

Jacoby, D.B., Youngson, R., 2005. Encyclopedia of family health, Marshall Cavendish.

Khosa, S.M., Usman, M., Moinuddin, M., Mehmood, H.O., Qamar, K., 2015. Comparative analysis of cellulose acetate hemoglobin electrophoresis and high performance liquid chromatography for quantitative determination of hemoglobin A2. Blood Res., 50(1): 46-50.

Kunkel, H.G.R., Ceppellini, R., Muller-Eberhard, U., 1957. “Observations on the minor basic hemoglobin component in the blood of normal individuals and patients with thalassemia.” J. Clin. Invest., 36(11): 1615-25. DOI: 10.1172/JCI10356.

Mosca, A., Paleari, R., Ivaldi, G., 2009. The role of haemoglobin A2 testing in the diagnosis of thalassaemias and related haemoglobinopathies. J. Clin Pathol., 62(1): 13-17. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.056945.

Muhammad, A., Farooq, M.U., Iqbal, M.N., Ali, S.,Ahmad, A. Irfan, M., 2013. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus type II in patients with hepatitis C and associated with other risk factors. Punjab Univ. J. Zool., 28(2): 69-75.

Muirhead, H., Perutz, M., 1963. Structure of reduced human hemoglobin. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

Nikam, S.V., Dama, S.B., Dama, L.B., Saraf, S.A., 2012. Geographical distribution and prevalence percentage of Thalassemia from Solapur, Maharashtra, India. DAV Int. J. Sci., 1(2): 91-95.

O’Donnell, J.T., Ahuja, G.D., 2005. Drug injury: Liability, analysis, and prevention, Lawyers & Judges Publishing Company.

Peter, T., Rowley, M.D., 1976. The diagnosis of beta‐thalassemia trait: A review. Am. J. Hematol., 1(1): 129-137.

Rachmilewitz, E.A. Giardina, P.J., 2011. How I treat thalassemia. Blood, 118(13): 3479-3488.

Rathod, D.A., Kaur, A., Patel et al., 2007. Usefulness of cell counter–based parameters and formulas in detection of β-thalassemia trait in areas of high prevalence. Am. J. Clin. Pathol., 128(4): 585-589.

Thomas, J.P., 2001. “beta-Thalassemia Minor and Newly Diagnosed Polycythemia Rubra Vera in a 71-Year-Old Woman.” Hosp. Physician., 37(4): 78-83.

Usman, M., Moinuddin, M., Ahmed, S.A., 2011. Role of iron deficiency anemia in the propagation of beta thalssemia gene. Korean J. Hematol., 46(1): 41-44. doi: 10.5045/kjh.2011.46.1.41.

Yamsri, S., Sanchaisuriya, K., Fucharoen, G., Sae-Ung, N., Fucharoen, S., 2011. Genotype and phenotype characterizations in a large cohort of β-thalassemia heterozygote with different forms of α-thalassemia in northeast Thailand. Blood Cells Mol. Dis., 47(2): 120-4.